Structural Integrity in Underwater Welded Structures

Introduction:

The world's oceans cradle a vast network of critical infrastructure – pipelines transporting energy resources, offshore platforms extracting oil and gas, and submerged tunnels facilitating transportation. A common thread uniting these structures is the essential role of underwater welding in their construction, maintenance, and repair. However, the very environment that these structures inhabit presents formidable challenges to achieving and maintaining structural integrity in welded joints. As mechanical engineers, we must meticulously consider the unique demands of the underwater realm to ensure the long-term safety and reliability of these vital assets. This blog post will explore the critical interplay between structural integrity and underwater welding, highlighting the key engineering challenges we face.

The Importance of Structural Integrity:

Structural integrity, in its essence, refers to the ability of a structure to withstand its intended loads and environmental conditions throughout its designed lifespan without failure. For underwater welded structures, this is paramount. Failure can lead to catastrophic consequences, including environmental disasters, economic losses, and, most critically, endangerment of human life, especially for divers and personnel working on or near these structures.

Achieving structural integrity in underwater welds is significantly more complex than in atmospheric welding. The hostile underwater environment introduces a multitude of factors that can compromise weld quality and long-term performance:

- Hydrostatic Pressure: The immense pressure at depth can affect the welding process itself, influencing arc stability, heat transfer, and even the metallurgical properties of the weld. Deeper water leads to greater pressure, exacerbating these effects.

- Water Quenching: Water acts as an extremely efficient heat sink. This rapid cooling rate associated with underwater welding can lead to:

- Increased Hardness: Rapid cooling can result in the formation of brittle metallurgical phases (like martensite in steel), increasing the risk of cracking and reducing ductility.

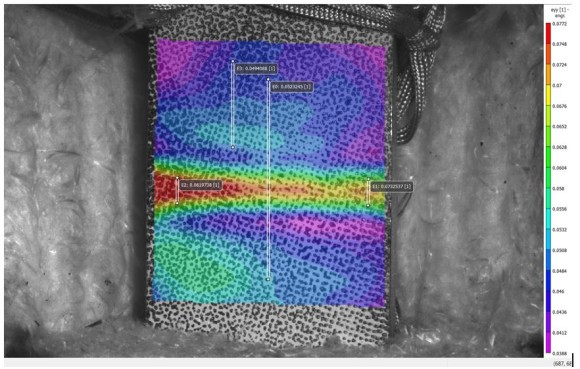

- Distortion and Residual Stress: Uneven cooling can induce significant residual stresses within the weld and the surrounding base metal, potentially leading to fatigue failure and stress corrosion cracking over time.

- Limited Visibility and Accessibility: Divers often work in murky, low-visibility conditions, sometimes in confined spaces. This significantly complicates the welding process, making precise control and manipulation of welding equipment challenging. Inspection of welds in these environments is also more difficult and less precise.

- Corrosion: Seawater is a highly corrosive environment, particularly for many structural metals. Underwater welds and the heat-affected zones (HAZ) can be particularly susceptible to various forms of corrosion, including galvanic corrosion, pitting corrosion, and crevice corrosion, weakening the structure over time.

- Fatigue Loading: Offshore structures are subjected to continuous cyclic loading from waves, currents, and sometimes operational vibrations. Underwater welds must be designed to withstand these fatigue loads without cracking or failing.

Engineering Challenges and Solutions:

Addressing these challenges requires a multifaceted engineering approach, encompassing:

-

Material Selection: Choosing materials that are inherently resistant to corrosion in seawater is the first line of defense. This often leads to the use of:

- Corrosion-Resistant Alloys: Stainless steels, duplex stainless steels, and nickel-based alloys offer superior corrosion resistance but can be more expensive and sometimes more challenging to weld.

- Carbon and Low Alloy Steels with Coatings: For many applications, carbon and low alloy steels are still preferred due to their cost-effectiveness and good mechanical properties. However, robust protective coatings (epoxy, polyurethane, etc.) and cathodic protection systems (sacrificial anodes or impressed current) are essential to mitigate corrosion.

-

Welding Process Selection and Optimization: The choice of welding process is critical and must be tailored to the specific application and underwater environment. Common underwater welding processes include:

- Shielded Metal Arc Welding (SMAW) – Wet Welding: Divers use waterproofed electrodes. This is the most economical and versatile method but generally produces welds of lower quality due to rapid quenching and hydrogen pickup in the weld metal. Primarily used for repairs where high structural integrity is not paramount or temporary fixes.

- Flux Cored Arc Welding (FCAW) – Wet Welding: Offers higher deposition rates than SMAW, but still suffers from similar issues related to wet welding environments.

- Gas Metal Arc Welding (GMAW) – Dry Welding (Hyperbaric): Welding is performed in a chamber sealed around the weld joint, filled with a breathable gas mixture, effectively creating a dry environment. This process yields higher quality welds, comparable to surface welding, but is more complex, costly, and depth-limited.

- Friction Stir Welding (FSW): A solid-state welding process that avoids melting, thus minimizing many of the problems associated with fusion welding underwater, particularly porosity and rapid cooling. FSW is gaining traction for certain underwater applications but has limitations in terms of joint geometry and material compatibility.

-

Welding Procedure Development: Rigorous welding procedures are essential, specifying:

- Welding parameters: Current, voltage, travel speed, electrode type, gas shielding (for dry welding), etc.

- Welding sequence: To minimize distortion and residual stress.

- Preheating and Interpass Temperature Control: Where feasible, preheating can reduce cooling rates and hydrogen cracking susceptibility. Interpass temperature control is important to manage heat buildup in multi-pass welds.

-

Non-Destructive Testing (NDT) and Inspection: Ensuring weld quality requires robust NDT methods, which are more challenging underwater:

- Visual Inspection (VT): Divers perform visual checks, but visibility limitations are a major constraint.

- Magnetic Particle Testing (MT): Effective for detecting surface cracks, but again, underwater application is complex.

- Ultrasonic Testing (UT): Widely used for subsurface defect detection and weld quality assessment. Underwater UT equipment and trained technicians are crucial.

- Radiographic Testing (RT): Less common underwater due to safety concerns and logistical complexities but can be employed in specific dry habitat scenarios.

-

Qualified Welders and Inspection Personnel: Underwater welding demands highly skilled and rigorously trained divers who are not only proficient welders but also understand the unique safety and operational challenges of the underwater environment. Similarly, NDT personnel must be qualified to perform inspections in challenging underwater conditions.

Conclusion:

Maintaining structural integrity in underwater welded structures is a continuous engineering ende✊avor. As we push deeper into the ocean for resource exploration and infrastructure development, the challenges intensify. Ongoing research and development are crucial in areas such as advanced welding processes, improved NDT techniques, and corrosion-resistant materials. By embracing a multidisciplinary approach, combining materials science, welding engineering, non-destructive testing, and skilled personnel, we can continue to ensure the safety and reliability of underwater welded structures that are vital to our modern world.

#UnderwaterWelding#StructuralIntegrity#MechanicalEngineering#WeldingChallenges #OffshoreEngineering #SubseaStructures #NDT #MaterialsEngineering #WeldingEngineering

References and Further Reading:

- American Welding Society (AWS) D3.6M:2017, Specification for Underwater Welding.

- International Standard ISO 15618-1:2016, Welding — Qualification testing of welders and welding operators for hyperbaric welding — Part 1: Welders.

- Koh, P.L., & Murchie, M.J. (2011). Underwater Wet Welding of Steel Structures: A Review. Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance, 20(6), 1035-1044.

- Bray, D.E., & McBride, D.I. (2018). Nondestructive Testing Techniques. John Wiley & Sons.

- Offshore Technology Conference (OTC) Proceedings – Papers related to underwater welding and structural integrity.

Comments

Post a Comment